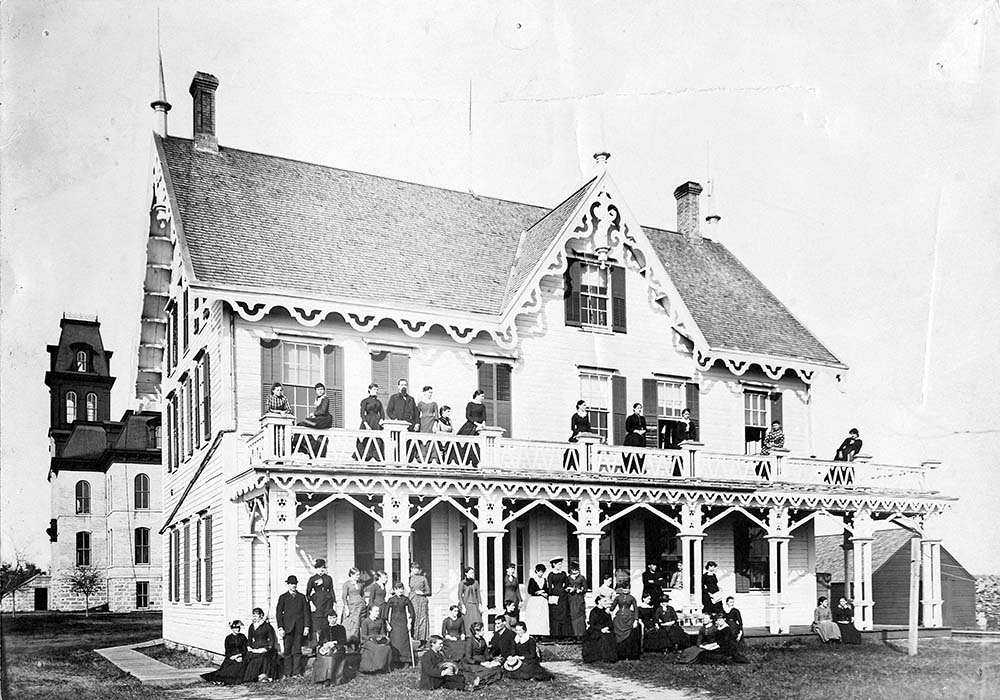

Stearns House

The spark that would lead to St. Cloud State’s founding was one of the first acts of the Minnesota legislature, which voted on Aug. 2, 1858 to direct the governor to appoint a board of instruction to establish three normal schools.

St. Cloud Normal School was the third school established by that legislative act, following the opening of schools in Winona in 1860 and Mankato in 1868.

The St. Cloud community provided the $5,000 needed to secure the site for the school. Stearns Hotel was chosen out of four sites considered by the State Normal School Board. The site, just north of where Riverview now stands, was chosen for its beautiful location on the bluffs over the Mississippi River and because the hotel, with just a few updates, could serve as a temporary school.

When the school opened Sept. 15, 1869, it was housed completely within the converted three-story hotel. It had a large open space for classes on the first floor, a two-classroom model school on the second floor and student living spaces on the third floor.

The first class of 50 students included 40 women and 10 men. Tuition was free for all students who agreed to teach in Minnesota for at least two years after graduation.

The curriculum was two years and covered subjects equivalent to the first two years of high school. True college-level courses wouldn’t be added until 1894.

The university’s early history is one of a struggle for funding and survival, opposition and advocacy. Then came growing pains, war, economic collapse and record enrollments as veterans returning from wars sought higher education, and the growing college strove to provide for the state’s needs beyond educating teachers.

A struggle for existence

Throughout the first decade, St. Cloud Normal School struggled for its existence. The first hurdle was the temporary nature of the Stearns Hotel as Gov. William Marshall continually vetoed funding for normal school construction. It wasn’t until 1873 when funds to build a permanent building were approved. Old Main opened in 1874 and would serve the institution through numerous expansions until 1948.

The second obstacle was opposition to normal schools on several fronts. Some opposed spending state funds on education. Others opposed state funding for high school-level education in just three communities — despite the majority of students at all three schools coming from outside of St. Cloud, Mankato and Winona. Private colleges opposed public funding for competitors, political in-fights and a lingering belief in an innate teaching ability kept the Normal School Board and St. Cloud’s resident board member busy advocating for the need for normal school education.

New century, new opportunities

The turn of the century brought with it growth for the St. Cloud Normal School with the rebuilding of Lawrence Hall after a 1905 fire, the addition of a second women’s dormitory Shoemaker Hall and a new model school building in 1906 with the opening of the Old Model School, which transitioned into a university library in 1911 with the opening of Riverview.

More to know

St. Cloud State renamed 51 Building, formerly the School of Business Webster Hall in her honor. Read about it

A witness to this growth was Ruby Cora Webster, the first known African American student to attend St. Cloud Normal School. She graduated in 1909 and was honored this October when the University renamed the former School of Business Building, also known as 51, Webster Hall in her honor. Along with the physical growth of campus was the increase in quality of the student body, by 1912 the normal schools were fighting for the right to award bachelor’s degrees, and high school classes were eliminated between 1915-1917.

Their efforts paid off and by 1921 the newly-named St. Cloud State Teachers College and the other state normal schools were authorized to grant bachelor’s degrees.

The United States’ entrance into World War I coincided with a drop in enrollment that reflected not only students leaving for war service, but also the elimination of secondary school courses and a demand for workers on the farms and in the war industry. The drop in enrollment was temporary, but the 1920s would signal the struggles that lay ahead for St. Cloud State Teachers College and its students as the Great Depression took hold.

In the 1920s students formed a variety of clubs and organizations including the Rho Tans, a student club for redheads formed in 1926, said Kasey Solomon, who studied St. Cloud State in the 1920s for a public history project.

“Students participated in clubs for academics, fine arts and athletics, but they also formed political and social groups that celebrated their different interests and identities,” she said. “Student organizations were a huge part of student life in the 1920s.”

The 1920s also saw a major push toward a four-year curriculum and the expansion of offerings to prepare students for junior high school, administration and special fields including industrial arts, physical education, music and fine arts.

As it did across the country, the Great Depression brought hardships to St. Cloud State Teachers College. Employee salaries were cut, tuition was charged for the first time and equipment, land purchases and construction were prohibited.

Enrollments dropped by a third as students found it difficult to pay for school. President George Selke instituted student work positions to help students stay in school by doing janitorial and clerical work, while others requested aid from the Emergency Relief Administration.

For the first time, graduates were having difficulty finding placements after graduation as practicing teachers delayed their marriage plans to stay in their positions and school boards increased class sizes, eliminated subjects and cut teacher rolls to cut tax rates.

The college established the Placement Bureau, a precursor to today’s Career Center, in 1928 to help new graduates and alumni secure work.

The harsh conditions of the Great Depression also proved a boon for St. Cloud State Teachers College as falling land prices and tax delinquencies freed up tracts of land near the college. During this time, St. Cloud State grew to include the Ervin House, Hilder

Quarry – now George Friedrich Park — and a number of the Beaver Islands.

It was also a time of growing interest in the wider world, said Kyle Imdieke, who studied the 1930s campus life for a public history project.

St. Cloud State’s first fraternity, Al Sirat, was founded in 1931 based on Muslim cultures instead of the usual Greek. And in 1933 a Muslim leader of India’s independence movement, Maulana Shakurat Ali visited St. Cloud and spoke on campus to more than 1,000 people as part of what the “Chronicle” described as the first lecture tour of the United States by a great Muslim leader.

There was also an interest in the original people of Minnesota with the attendance of the school’s first known Native American students Lillian Eveln Moore, described as being of Sioux descent, and Alma Lillian Baird, of Oneida descent. Baird became an advocate of Native American cultures on campus before her graduation, when she took a position at a Case County school.

Hardship and service

World War II brought with it the largest drop in enrollment in school history as men left for the service and women left for high paying jobs in business and industry.

George Selke

George Selke was one of the Monuments Men during World War II Read about it

Faculty left to serve in the war and for military research and civilian defense positions. Among them was President Selke who would become one of the Monuments Men tasked with protecting cultural property in war areas.

Prior to leaving for service, Selke anticipated the drop in enrollment a war would bring and sought to find a role for St. Cloud State in the war effort.

The college contracted with the federal government to train pilots for the Civilian Pilot Training course, worked to train B-1 Naval program men prior to entry into active military service, and contracted with the Western Flying Training Command of the Army Air Force to house and train military personnel in physics, mathematics, physical education, history, geography and English.

St. Cloud State’s efforts earned it a Certificate of Award for meritorious service rendered to the Army Air Forces.

The campus supported the war efforts in other ways as well. Faculty and student committees promoted the sale of war stamps and bonds and collected scrap metal and tin cans.

The 1942 Homecoming saw the dedication of a service flag, and students participated in Red Cross activities, served in the USO canteen and donated blood. War became a focus in the classroom as well with students studying war and post-war problems.

The student efforts stood out to history student Kayla Stielow who researched student life on campus during the 1940s for her public history course and master’s thesis.

“Between helping with home front based activities, finding ways to both promote and help each other to both follow and live with wartime rationing, as well as the student’s belief that becoming educated and receiving their degrees would help them continue to serve their country and their community even after the war would end, the students really took on personal responsibility for assisting with the war and mobilized the campus,” she said.

To help with morale as students worried about classmates, family members and friends in the service, St. Cloud State organized a speaker’s bureau to issue war information and victory books and offered correspondence for students and alumni serving in the war.

The college celebrated its 75th anniversary in October 1944 with a week-long celebration in conjunction with homecoming featuring presentations by faculty and students each day.

Participating were six Japanese-American students who were attending St. Cloud State as part of a program for college-age Japanese Americans to attend classes in lieu of internment.

The war’s end was heralded with the listing in the 1946 Talahi, a student yearbook, of the names of 32 students who had died in service and three listed as missing in action. Before long St. Cloud State was serving veterans returning from the war.

Post-war boom

Enrollments doubled pre-war numbers in the late 1940s as St. Cloud State and other teacher’s colleges stepped up to meet demand after the University of Minnesota called a conference to find solutions as applications there vastly outpaced its capacity.

This post-war veterans’ boom was St. Cloud State’s first step out of the realm of teachers college to begin offering pre-professional programs in other disciplines.

Business was the most popular subject comprising 20 percent of the student population and foreshadowing the important place the Herberger Business School now holds on campus. St. Cloud State also supported World War II veterans by working with the Veteran’s Administration to set up a testing, counseling and guidance bureau on campus to advise returning veterans about their employment and college and vocational training options.

This also began another period of growth as the campus moved out of Old Main and into Stewart Hall, Kiehle library was built in 1952 and veterans married housing was opened on Selke Field in 1947.

With the further expansion of careers outside of teaching to include journalism, audio visual education and drama, the college sought to drop “Teachers” from its name. The request was granted in 1957 for all the state teachers colleges. The college reorganized in 1962 to establish the schools of Education; Business and Industrial Arts; and Science, Literature and Arts.

The campus footprint grew dramatically from 1957-1965 with the addition of eight buildings and additional expansions to existing buildings. The buildings were needed as enrollment leapt from 2,060 students in 1952 to 6,729 in 1965.

In the midst of all this growth students furthered their own knowledge through debate and student activities.

“There was a major debate on the relationship between religion and science that happened in the editorial section of the College Chronicle,” said Blake Johnson, a public history graduate student who studied 1950s student life at St. Cloud State. “It was interesting to look back and see what ideas were popular and that the student body was willing to discuss differing points of view in a way that we don’t see as much. Namely, the use of the newspaper.”

This growth continued throughout the 1960s at a time when events and student activism was also growing, said Lance Sternberg, who studied St. Cloud State in the 1960s for a public history class.

“Events on campus and student activism reached feverous heights when it came to hot button issues such as Vietnam and Civil Rights,” he said. “Some of these events may seem surprising to us now, as we look back, but I really found the student community to be a microcosm of society at large. Just like we could expect, and have experienced during current times.”

As the university closed out its first 100 years, it celebrated its centennial under the theme “A Heritage of Excellence” and kicked off the celebration with the groundbreaking of its newest building — a new library to be named Centennial Hall.

The first 100 years took St. Cloud State through some rough years and saw it grow in quality and reputation as it sought to serve the state of Minnesota and adapt to the needs of the state and its citizens.

Learn about St. Cloud State’s continued growth in part II: 1969-2019 in the next edition of St. Cloud State University Magazine.

Sources: “History of St. Cloud State Teachers College” by Dudley S. Brainard and “A Centennial History of St. Cloud State College” by by Dr. Edwin Cates.